Senegal: Casamance Was Worth the Wait!!

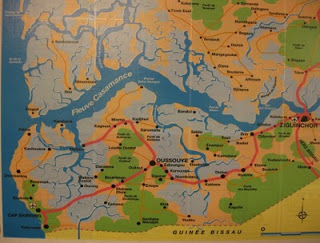

Map of the lower Casamance River showing all the mangrove tributaries. Ziguinchor is on the lower right side of the map, and our final destination, Point St. George, is at the upward bend of the river in the middle of the map. The Dakar to Ziguinchor ferry… a really nice boat!

The Dakar to Ziguinchor ferry… a really nice boat!

Mangroves viewed from the ferry

Mangroves viewed from the ferry Bottlenose dolphins leaping everywhere!!

Bottlenose dolphins leaping everywhere!!

My first view of Ziguinchor. It’s a pretty and sleepy fishing town, and it would be hard to believe there’s recently been trouble there, except that we saw lots of military everywhere in town.

The mummified manatee head. The next morning we arranged a car to take us back downriver to the fishing town of Elinkine, where we met El Hadj, who, with his brother Oussman, works for Oceanium Dakar and is working to establish a protected area for manatees in Point St George on the Casamance River. El Hadj took us by boat to Point St George, a trip of about 2 hours through the mangroves. Pt. St George is of particular interest for manatees, because there’s a small freshwater spring just offshore and manatees come there to drink everyday. Sometimes up to 30 manatees a day visit the spring, the largest gathering spot I’ve heard of in Africa (which is why I’d been trying to get here for a year!). The Casamance River is extremely salty, infact the salinity is higher than the ocean. Manatees don’t get all the freshwater they need from the food they eat, so they need to drink freshwater periodically. Studies of Florida manatees indicate that manatees living in saltwater usually travel to a freshwater source to drink approximately once a week.

The next morning we arranged a car to take us back downriver to the fishing town of Elinkine, where we met El Hadj, who, with his brother Oussman, works for Oceanium Dakar and is working to establish a protected area for manatees in Point St George on the Casamance River. El Hadj took us by boat to Point St George, a trip of about 2 hours through the mangroves. Pt. St George is of particular interest for manatees, because there’s a small freshwater spring just offshore and manatees come there to drink everyday. Sometimes up to 30 manatees a day visit the spring, the largest gathering spot I’ve heard of in Africa (which is why I’d been trying to get here for a year!). The Casamance River is extremely salty, infact the salinity is higher than the ocean. Manatees don’t get all the freshwater they need from the food they eat, so they need to drink freshwater periodically. Studies of Florida manatees indicate that manatees living in saltwater usually travel to a freshwater source to drink approximately once a week.

Our host Oussman’s house in Pt. St. George.

Pt. St. George already attracts a few tourists who come to see the manatees. This sign (Manatee ecology path) was in the center of the village.

The manatee viewing tower seen from the Pt St George beach.

The manatee viewing tower seen from the Pt St George beach.

Closeup of the tower. At high tide the water comes up past the base of the tower. At low tide it sits at the shoreline and the spring is about 50 meters offshore, within the river.

Closeup of the tower. At high tide the water comes up past the base of the tower. At low tide it sits at the shoreline and the spring is about 50 meters offshore, within the river.

View of the beach from the top of the tower.

View of the beach from the top of the tower.

View of the main river from the tower, with the approximate location of the spring shown by the red arrow.

View of the main river from the tower, with the approximate location of the spring shown by the red arrow. Lots of manatee noses popped up at the spring during low tides. An Oceanium student intern who worked here started a rudimentary photo ID catalog for individual manatees based on scar patterns on their tails. He identified about 15 different individuals. I plan to train Senegalese biologists to continue and expand this work in order to get a better idea of the population.

Lots of manatee noses popped up at the spring during low tides. An Oceanium student intern who worked here started a rudimentary photo ID catalog for individual manatees based on scar patterns on their tails. He identified about 15 different individuals. I plan to train Senegalese biologists to continue and expand this work in order to get a better idea of the population. Manatee tail fluke diving back down to the spring.

Manatee tail fluke diving back down to the spring.

This manatee’s tail is covered with both barnacles and mud. Manatees get barnacles all over their bodies if the spend alot of time in saltwater. The mud is likely from the manatee rolling on the bottom. In Florida we see this behavior during the winter, when the manatees “burrow” their heads into the warmer mud at the bottom of warm water locations, but I’m not sure why these manatees are rolling. Maybe they’re trying to rub off the barnacles. The water here was very warm- 26 degrees Celcius.

This manatee’s tail is covered with both barnacles and mud. Manatees get barnacles all over their bodies if the spend alot of time in saltwater. The mud is likely from the manatee rolling on the bottom. In Florida we see this behavior during the winter, when the manatees “burrow” their heads into the warmer mud at the bottom of warm water locations, but I’m not sure why these manatees are rolling. Maybe they’re trying to rub off the barnacles. The water here was very warm- 26 degrees Celcius.

Mother and calf manatees diving. This was my first verified sighting of a West African manatee calf!

Mother and calf manatees diving. This was my first verified sighting of a West African manatee calf! As I mentioned, there were LOTS of big jellyfish in the river and many others dead on the beach. I’m not sure if this was normal or not, but they were beautiful (although it was eerie swimming in the murky water knowing they were there)

As I mentioned, there were LOTS of big jellyfish in the river and many others dead on the beach. I’m not sure if this was normal or not, but they were beautiful (although it was eerie swimming in the murky water knowing they were there)

I snorkeled out to the manatee spring to check the depth and salinity at low tide. I also listened for manatee vocalizations, but didn’t hear any, even though I’m pretty sure there were a few in the area.

I snorkeled out to the manatee spring to check the depth and salinity at low tide. I also listened for manatee vocalizations, but didn’t hear any, even though I’m pretty sure there were a few in the area.

The village has buoys provided by Oceanium to mark the spring as a protected area, but they weren’t in the water while we were there, and we watched several boats go right over the manatees. I will be providing recommendations to Oceanium for future conservation activities, and the first will be to put the buoys back in the water and connect them with cords so that boats can’t enter the spring area!

While in Pt St George El Hadj and Oussman took us on boat excursions along the mangroves to look for manatee feeding sign, and to clam flats where manatees feed (yes, here as in several other places in Africa, manatees are known to eat clams- the proof has been found in stomach samples from dead manatees).

While in Pt St George El Hadj and Oussman took us on boat excursions along the mangroves to look for manatee feeding sign, and to clam flats where manatees feed (yes, here as in several other places in Africa, manatees are known to eat clams- the proof has been found in stomach samples from dead manatees). Mangrove branch with cropped leaves eaten by manatees.

Mangrove branch with cropped leaves eaten by manatees.  This is the species of clam manatees eat in Casamance (Adrana senilis).

This is the species of clam manatees eat in Casamance (Adrana senilis).

El Hadj and Oussman’s father was a manatee hunter and they still had an old skull, which they gave me for my genetics research.

El Hadj and Oussman’s father was a manatee hunter and they still had an old skull, which they gave me for my genetics research.

On our return trip to Elinkine, El Hadj showed me his father’s old manatee harpoons. Culturally, manatee hunters are well-respected in Africa, and the tradition is often passed from father to son, so El Hadj is proud to own these, although luckily he doesn’t use them!

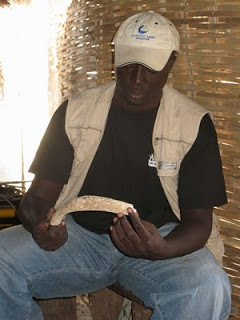

Tomas checks out a very old manatee rib that El Hadj also gave me.

Tomas checks out a very old manatee rib that El Hadj also gave me.

At the end of our trip we returned to Ziguinchor and boarded the ferry for another overnight trip to Dakar, although this time we had cabins which made the journey much more enjoyable! We sailed out of the Casamance River into the Atlantic Ocean at sunset. In Diogue, the village at the river mouth, people say they see manatees swimming in the ocean. This isn’t surpising given the large number of mangrove channels in the area. El Hadj also volunteered that there are aquatic plants in the sea that manatees like to eat. You can bet I’ll check that out next time!

At the end of our trip we returned to Ziguinchor and boarded the ferry for another overnight trip to Dakar, although this time we had cabins which made the journey much more enjoyable! We sailed out of the Casamance River into the Atlantic Ocean at sunset. In Diogue, the village at the river mouth, people say they see manatees swimming in the ocean. This isn’t surpising given the large number of mangrove channels in the area. El Hadj also volunteered that there are aquatic plants in the sea that manatees like to eat. You can bet I’ll check that out next time!

This is definitely not the last I will see of the Casamance manatees, I’m looking forward to working with Oceanium Dakar and the Pt. St George community to develop a long-term conservation and research project there!

This is definitely not the last I will see of the Casamance manatees, I’m looking forward to working with Oceanium Dakar and the Pt. St George community to develop a long-term conservation and research project there!