Following the Manatee Trail

Back in 2009 I tagged three manatees in the Senegal River as part of a collaborative study with my colleagues from CBD- Habitat (a Spanish NGO) and Oceanium Dakar (a Senegalese NGO). You can see my original post about it here. It was the first time West African manatees had ever been tagged with satellite-linked tags, and we learned alot about their dry season movements in the eastern Senegal River, work which I plan to continue (more on that later). However, because the 2009 tagging was an opportunity that arose unexpectedly as a result of manatees becoming trapped behind an agricultural dam and needing to be rescued, we didn’t have a budget for tracking them in the field once they were released. You can learn some great things from satellite data, but what you don’t get is information about manatee behavior. We know where they went, but there were no field observations to determine what they did at each place, how many other manatees they might have been with, etc. At the time we knew that getting some basic first information about the manatees’ habitat use was better than nothing (after all, no one had ever satellite tagged them before), and we assumed that after being trapped for months with almost no food they would probably go to feeding locations, but ever since I’ve been curious to check out some of the places they chose to go while tagged. Last week I finally got the chance.

After finishing up the necropsies and a very productive meeting with the local Water and Forestry Dept., we left Matam very early in the morning last Tuesday and headed north back up the road that eventually leads to Dakar. After about 2 hours we left the main road and headed off east on a sand track. We brought a guide with us who knew the area where we were headed because he grew up in one of the villages, otherwise it would’ve been unwise to drive off the only real road into such an immense and remote desert. There are no signs and many tracks through the brush, so you really need to know where you’re going. Acacia bushes are everywhere and have huge spines that can easily puncture tires. So few outsiders ever venture to this area that people run in terror from the sight of a car (it literally might as well be a space ship), and teenage girls are afraid because they’ve never seen a white person before.

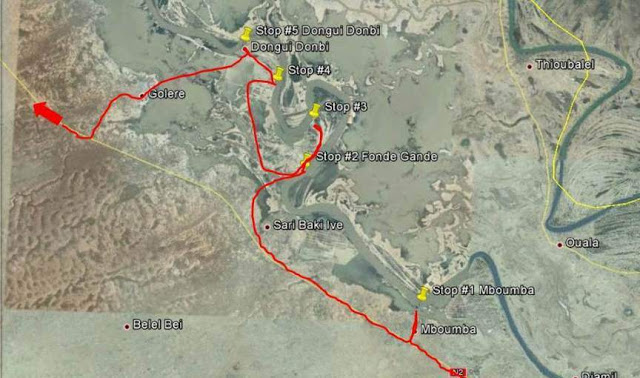

I was armed with maps of our two male manatee tag locations from this area, and was hoping to be able to drive along the Senegal River. I quickly realized that this wasn’t going to be possible. The Senegal River floods an insanely huge area every rainy season (over 30 miles wide in some places) but shrinks down to a tiny river barely a half mile wide during the dry season. So roads and villages that sit on the edge of the floodplain are miles away from the river during the dry season. And even when you reach the river’s edge, it’s prime land for farms, so no tracks run directly along it. Instead we went to villages and other points along the river where we were able to see places where our red tagged manatee had been.

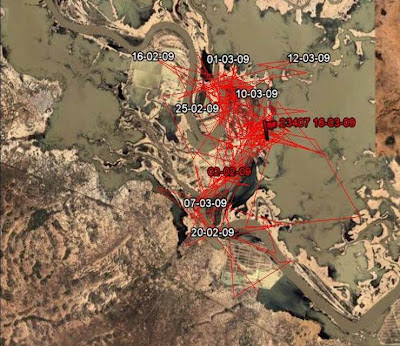

Here’s a map of one month worth of manatee locations from 2009. This manatee moved directly to this small area (only a couple miles wide) as soon as he was released, and stayed here for 4 months. The thin strip of grey in the center is the river during the dry season, the larger grey areas around it are flood zones (Map courtesy of CBD-Habitat).

No Comments